Picking Up the Pace of Change: California’s Results in the 2017 Long-Term Services and Supports Scorecard

summary

California maintained its rank at No. 9, but it must do more to keep up with the growth of the older adult population. This brief highlights trends in California’s performance and opportunities to improve its rate of progress.

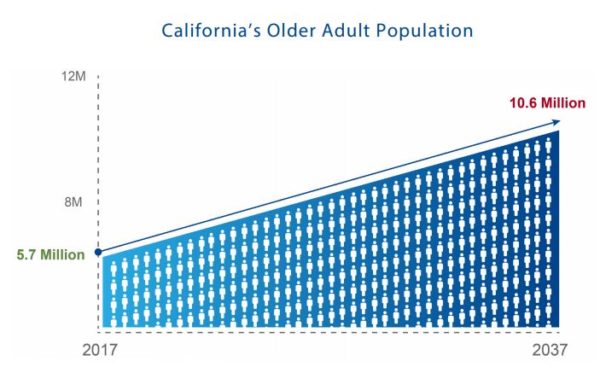

Date Updated: 07/07/2017California maintained its rank at No. 9, but the state must prepare to keep up with the growth of the older adult population, expected to nearly double by 2037. This brief highlights trends in California’s performance and opportunities to improve progress.

Introduction

This June, the AARP Public Policy Institute released a third comparison of state long-term services and supports (LTSS) systems that reveals performance gains and losses in five specific dimensions. Titled, Picking Up The Pace of Change: A State Scorecard on Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Adults, People with Physical Disabilities, and Family Caregivers (Scorecard), results show that progress is slow, especially in context of the rapidly increasing older adult population.1 In California, the population of people age 65 and older is expected to nearly double by 2037 with escalating growth thereafter.2 To keep up with the growth of California’s older adult population, it is time to make LTSS system improvement a priority and pick up the pace of progress. Based on the Scorecard findings, this brief explores what the state should do to prepare for California’s aging population.

California’s Scorecard Performance

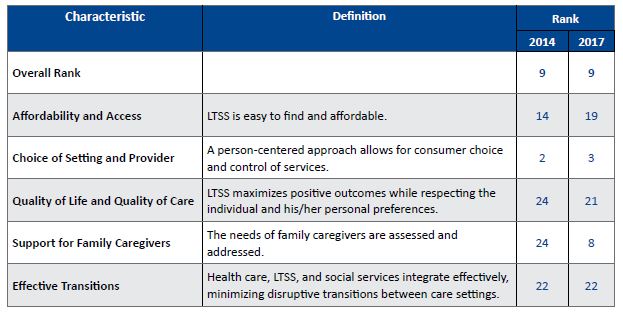

The Scorecard shows that California maintained its ranking at No. 9 across all 50 states and theDistrict of Columbia. Relative to other states, California made gains in two dimensions and lost ground in two dimensions.1

Table 1: California’s Ranking in Characteristics of a High-Performing LTSS System, 2017

Note: Methodology for the Scorecard rankings can be found at www.longtermscorecard.org

Affordability and Access (Ranked No. 19)

The cost of LTSS is unaffordable for most Californians, limiting access to services. In California, the annual cost of 30 hours per week of home care is almost $36,000, or three-quarters of median household income. The median annual cost of nursing home care is $112,055, more than two times of median household income. The primary payers for these services are individuals (i.e., outof-pocket costs) and Medi-Cal, which requires that people be impoverished for eligibility. Limited uptake of private long-term care insurance currently adds to the challenge, as only 5 percent of Californians age 40 and older have purchased coverage.1

Choice of Setting and Provider (Ranked No. 3)

Californians overwhelmingly prefer to remain in the community. Access to home and community-based services (HCBS) and affordable housing options are essential to meeting the needs of our state’s changing population. California is lagging behind the top-ranked state in LTSS spending focused on HCBS—58 percent compared to 69 percent. An important part of this equation is the need for affordable housing. California’s supply of assisted living options has not kept pace with the age 75 and older population, who could benefit from its availability. Additionally, just 6 percent of all housing units are subsidized, a significant challenge to meeting the need of the growing demographic.

Quality of Life and Quality of Care (Ranked No. 21)

California must ensure high quality care for people needing services in either institutional or community-based settings. California’s rate of pressure sores among nursing home residents is double that of the best-performing state, and made no significant improvement between scorecards. The report also calls out a lack of standardized quality measures collected for HCBS, despite longstanding federal efforts to ensure older adults and people with disabilities have options to receive supports in community settings.1

Support for Family Caregivers (Ranked No. 8)

California must elevate policies to support unpaid family caregivers, better serve the needs of older adults, and promote greater efficiencies in public spending. Nearly 4.5 million unpaid caregivers provide support to family members, friends and neighbors in our state, valued at $57 billion annually.3 California has enacted several policies among those measured, but continues to rank among the last in nurse delegation and scope of practice policies. Of the health maintenance tasks reviewed, California permits privately-paid home care workers to perform only two (administer glucometer tests and enemas). Nearly one-third of all states allow paid home care workers to perform numerous tasks, mostly related to administering medication.1

Effective Transitions (Ranked No. 22)

California must create opportunities to safely transition individuals from institutional settings to the community. Nearly 1 in 10 California nursing home residents have low care needs, compared to 1 in 25 in the top-ranked state. Additionally, twice as many Californians newly admitted to a nursing home will stay longer than 100 days as compared to people in the top-ranked state, creating risk for institutionalization.1

Recommendations for California’s Leaders

Efforts to transform California’s LTSS system must address system challenges as a whole. The following five actions would help the state accelerate the pace toward improved system performance and quality of life for Californians needing help with routine activities in their daily lives.

- Articulate a strategy to strengthen California’s LTSS infrastructure. California needs strong leadership and a clear picture of its goals and objectives for an aging population in light of the critical demographic shift, federal efforts toward more integrated systems of care, and the need for sound LTSS financing solutions. A clear commitment and well-articulated vision is needed to prepare for demands across a variety of sectors including health care and LTSS infrastructure, workforce, and financing.

- Promote assessments and care planning that connect people to the right services at the right time in order to avoid unnecessary hospitalizations and nursing home stays. Individuals draw support from a variety of interacting service systems beyond health care (e.g., social services, housing, legal). However, each of these systems carries its own assessment process—often leading consumers in multiple directions in an uncoordinated fashion. A single, coordinated assessment would improve access to services, quality of care, planning for one’s goals and future needs, as well as facilitate smooth transitions between levels of care. This process should also include caregiver-specific items to better identify and support the needs of family caregivers who often bear the primary care coordination responsibility for their loved ones.

- Increase access to housing so people with daily needs can live in the setting of their choice. To ensure low-income older adults and people with disabilities have real choice of where they receive services, the state and local communities must work with federal programs to increase the supply of affordable housing options. Under Medi-Cal, the state should expand participation in the Assisted Living Waiver. State and local entities should also encourage housing developers to utilize tax incentives to expand access to affordable housing options.

- Reduce barriers for family caregivers to provide care. In California, three actions are critical to avoiding burnout, and improving health and economic security of family caregivers:

- assessing family caregiver need when assessing individuals for public LTSS programs;

- protecting family caregivers from employment discrimination; and

- allowing nurses to delegate more tasks to qualified home health aides, thereby reducing system costs and relieving caregiver burden.

- Support working families in planning for future daily living needs. No state or federal financing system exists for LTSS beyond Medicaid, which is not available to people until they are impoverished and is currently facing major reform. State and federal action is needed to enable working families of today to plan and pay for their daily care needs of tomorrow.

Conclusion

California’s standing among the top-performing states for LTSS is largely a byproduct of: 1) In-Home Supportive Services, California’s self-directed personal attendant program; and 2) new enacted laws that support working family caregivers. However, rapid growth in the number of older adults and people with disabilities who will need services, and the substantial decline in the availability of unpaid caregivers over the next few decades necessitate a new call for picking up the pace of change. It will take decisive leadership, a clear vision for the LTSS system of tomorrow, and a clear pathway on how to achieve this vision for our Californians living and aging with daily needs.

Download the publication for all visuals and complete references.

Continue Reading

The SCAN Foundation aims to identify models of care that bridge medical care and supportive service systems in an effort to meet people’s needs, values, and preferences. Care coordination is a central component of this vision, which ultimately leads to more person-centered care. This brief outlines The SCAN Foundation’s vision for care coordination in a person-centered, organized system.

This policy brief describes California’s results in the 2014 Long-Term Services and Supports State Scorecard, identifying areas for improvement as well as policy opportunities to transform and improve the state’s system of care.

To succeed in this era of health system transformation, plans and providers bearing risk – in an accountable care organization (ACO) for example – will need strategies for managing a broad array of care needs for high-risk beneficiaries across multiple settings of care. Download this fact sheet to learn more.