Looking Forward: Top Seven Recommendations to Improve Integrated Care in California

summary

Drawing from four years of Cal MediConnect evaluation results, this brief highlights recommendations for policymakers and health plans to consider in improving integrated systems of care for people with Medicare and Medicaid.

Date Updated: 12/19/2018Introduction

California is one of 10 states implementing a capitated model of care through the federal Financial Alignment Initiative, which integrates all Medicare and Medicaid-covered services— including specified long-term services and supports (LTSS).1 California’s demonstration, called Cal MediConnect (CMC), has approximately 115,000 dually eligible individuals enrolled in seven participating counties—more than any other state.2 Throughout implementation, The SCAN Foundation has funded regular polling and a broad evaluation of CMC by the University of California. The university gathered real-time feedback from approximately 20,000 dual eligible individuals to monitor their experience of care, determine what is working and what is not, and help drive needed improvements.3,4

Results have provided point-in-time information and perspective on whether beneficiary experiences changed during CMC’s implementation. In fact, with overall satisfaction increasing from 89 percent in 2016 to 94 percent in 2017, CMC enrollees reported higher satisfaction than those opting out in the areas of provider relationship, communication, and benefit explanation provided by the health plans.3,4 Enrollees also reported longer relationships with their personal doctor, a key indicator of care continuity that is especially important after a transition to managed care.4 Other positive outcomes include decreased emergency department visits for CMC enrollees from 2016 to 2017, and improved access to various services for a quarter of individuals after switching to CMC.3 Additionally, when issues have been brought to light, the California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) elevated evaluation findings and responded with a series of recommended policies to drive system improvements including:

- Adding 10 mandatory LTSS-related questions to Health Risk Assessments (HRA) —

administered by health plans to assess for individuals’ needs and risk; - Requiring CMC plans to provide unlimited non-emergency transportation;

- Extending the continuity of care provisions for an individual to keep an out-of-network doctor

when transitioning to CMC from six to 12 months; and - Revising the CMC beneficiary toolkit to make it easier to understand.

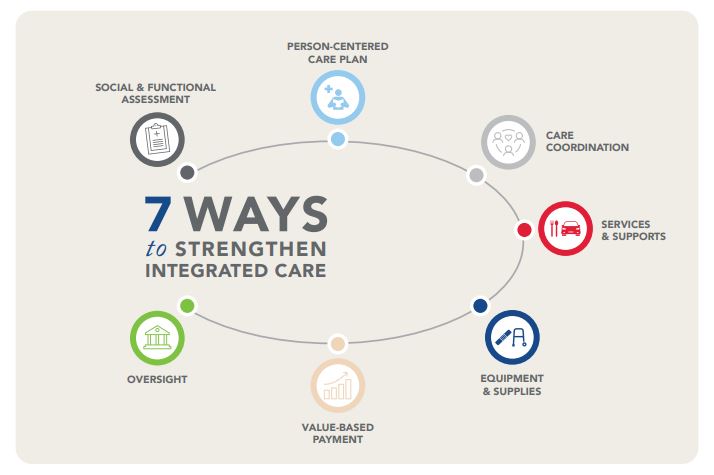

The evaluation findings also highlight continued areas of opportunity for program refinements to further improve the care delivery system for dual eligible individuals, especially relating to care coordination and addressing LTSS need. California is at a critical juncture as the state transitions to a new administration and considers the future of CMC. The CMC evaluation provides the incoming administration and Legislature an opportunity to strengthen CMC while developing a high-quality, integrated service delivery system for older adults and people with disabilities. As the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the state, and health plans are negotiating a plan to extend the demonstration, the following seven recommendations stand out among the CMC evaluation results.

Recommendations

- Assess all beneficiaries’ LTSS needs, including unmet needs. In a high-quality system of integrated care, an individual’s medical and non-medical needs and goals are identified for care planning.5 In 2017, 25 percent of CMC enrollees reported the need for more help with personal care, and 37 percent needed help with routine tasks. These unmet needs resulted in serious consequences, such as medication errors, inability to get out of bed, and isolation.3 Unmet need is even higher for people who opted out of CMC, more of whom report using specialized equipment and needing assistance with daily tasks.4 Health plans have demonstrated success in addressing individuals’ medical needs, but continued attention is warranted to identify non-medical needs and connect people to LTSS, including care plan option services. Toward that end, DHCS required Medicaid plans to include 10 questions in the HRA to identify functional and social support needs beginning in 2018.6,7 However, additional guidance is needed regarding how to use the data to inform care planning, and what should be reported to the state. Questions to consider include: when identified, what unmet needs are the plans accountable for? What is the timeline for addressing unmet needs? And what oversight exists? We recommend that DHCS provide clear guidance to the health plans regarding expectations of how to use the data to improve care planning and care coordination, and how the data can be regularly monitored to address unmet needs both for the individual and for program planning by the health plans and the state.

- Provide guidance and adopt standards to ensure care plans reflect an individual’s expressed needs, goals, and preferences. While health plans report that 70 percent of high-risk CMC beneficiaries had an individualized care plan (ICP) within 30 days of HRA completion, only half of CMC beneficiaries surveyed for the CMC evaluation remembered receiving an ICP in the mail.3,8 Of those, only half said the ICP included information they found important.3 The three-way contracts between DHCS, CMS, and health plans require ICPs to be comprehensive and person-centered, including a person’s goals and preferences.9 We recommend that DHCS more closely monitor health plans’ ICP processes and content, and work with plans and stakeholders to develop strategies to ensure care plans are truly person-centered.

- Refine care coordination protocols to best meet the needs of high-risk beneficiaries. Individuals dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid are more likely to have complex care needs, experience significant functional and cognitive impairments, and have greater need for care coordination.10 The University of California evaluation shows that care coordination provided in CMC is working well for those who receive it—yet there is no clear pattern as to who receives it.3 And while some enrollees report having access to a nurse, social worker, or other health plan staff as a single point of contact, other individuals report having to deal with multiple care managers throughout the service system. A 2016 report highlights tactics for high quality integrated care that include varying care coordination intensity according to assessed need and having a primary care coordinator as a single point of accountability.11 Building on recommendations for federal action, we recommend that DHCS ensure health plans establish protocols to help people access the right level of care coordination to meet their needs. We recommend that DHCS ensure health plans require more intensive care coordination that includes comprehensive assessments, more frequent contacts, and referrals to existing support services to better address high need.

- Develop strategies to address unmet LTSS need. Of the CMC enrollees and opt-outs with LTSS needs, over half have personal care needs and about four of every five need help with routine tasks.4 As part of their care coordination responsibilities, health plans play an important role in connecting enrollees with necessary Medi-Cal and non-Medi-Cal funded services and supports. Nearly a quarter of CMC enrollees who use IHSS reported they received help from their CMC plan to enroll in IHSS or increase their hours. However, the rate of referrals and provision of Care Plan Options that CMC plans can pay for is unclear. CMC enrollees are not eligible for Assisted Living Waiver services, and support in an assisted living facility or additional IHSS hours beyond the state cap would have to be funded by the CMC plan through Care Plan Options. These services are not included in the rate-setting calculations for the health plans. Additionally, CMC enrollees living in assisted living facilities are categorized at the lowest risk level by the state, which in turn affects the CMC plan’s payment rate.12 The CMC plans have little financial incentive to provide Care Plan Option services for additional support as current regulations result in plans being paid less for these individuals while paying for services that are not reimbursable. We recommend that DHCS specify scope of responsibility and benchmarks for both Medi-Cal and non-Medi-Cal funded LTSS referrals and utilization, and change state policies to increase access to waiver services for CMC enrollees.

- Identify and address barriers to accessing durable medical equipment (DME). For individuals who need assistance with daily activities, DME serves to improve safety, independence, and quality of life. The percentage of CMC beneficiaries reporting unmet DME needs increased from 7 percent in 2016 to 23 percent in 2017, while individuals who opted out reported no change. Unmet needs included lack of access to wheelchairs, breathing equipment, and incontinence supplies. Beneficiaries with a care coordinator were more likely to get assistance addressing their DME needs.3 We recommend that CMS, DHCS, and health plans work together with stakeholders to identify barriers to develop and pilot innovative solutions to DME access.

- Refine value-based payment strategies for CMC and managed care to achieve better LTSS outcomes. Payment should be aligned with quality measures that address what matters most to people; this will drive care to be delivered in a person-centered manner. In CMC, incentives to improve quality of care resulted in plans increasing oversight of providers. However, the increased collection and reporting of quality metrics connected with CMC also creates burdens for both health plans and providers.13 With growing interest in value-based payment strategies for LTSS, researchers have developed tools for states to better shape these models and select performance measurements. We recommend that DHCS refine value-based payment tools and work with health plans to improve access to and coordination of LTSS.

- Apply stronger oversight of health plan practices to ensure enrollees’ rights and well-being. Throughout the demonstration CMS and DHCS have acted on various consumer protections, providing guidance and clarification to health plans. For example, in a 2016 provider bulletin, DHCS addressed the issue of balance billing where individuals wrongly receive bills for services covered by Medicare and Medi-Cal.14 Consumer education materials were also made available in 2017.14,15 However, a 2018 CMC evaluation revealed that one of every five CMC beneficiaries was notified of unpaid bills. Providers are to accept as payment in full the combined amount that Medicare and Medi-Cal pays them. As such, dual eligible beneficiaries should never receive bills for any remaining balance.3,16 The evaluation revealed other issues, such as half of non-English speaking beneficiaries reporting that a medical interpreter was not provided when requested. Issues like these impede a person’s rights and interrupt quality of care. We recommend that DHCS monitor deficiencies through periodic beneficiary surveys and work with health plans to ensure consumers are not improperly billed for services rendered and have access to culturally appropriate services.

Conclusion

Improving the system of care for California’s dual eligible individuals will move the state closer to achieving person-centered service delivery. The CMC evaluation has informed efforts by the state, CMS, and health plans to drive system improvements throughout the demonstration. In its recent evaluation of California’s implementation of the Financial Alignment Initiative, RTI referenced the University of California CMC evaluation results. Building on this first report, RTI anticipates analyzing encounter data in the future to report on utilization measures.17 Additionally, the University of California will continue to analyze the data previously collected to improve understanding of dual eligible individuals’ experiences in Cal MediConnect counties. State and federal policymakers and health plans should use this new information combined with what is already collected and work with stakeholders to strengthen California’s system of integrated care.

Download the publication for all visuals and complete references.

Continue Reading

This policy brief establishes a basis for the critical system transformation activities necessary to produce a high quality, person-centered system of care for older adults and people with disabilities.

This fact sheet provides the background and context for California’s Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI), established as part of the enacted 2012-2013 budget. It outlines the changes to the delivery of medical care and longterm services and supports (LTSS) for individuals eligible for Medicare and Medi-Cal as well as Medi-Cal-only seniors and people with disabilities initiated by the CCI.

This is the third report coming from the California Medicaid Research Institute (CAMRI) project entitled: Comprehensive Analysis of Home- and Community-Based Services in California. The report describes Medicare and Medi-Cal spending for those beneficiaries using long-term services and supports funded by Medi-Cal.