Advancing Action: California’s Performance in the 2020 Long-Term Services and Supports State Scorecard

summary

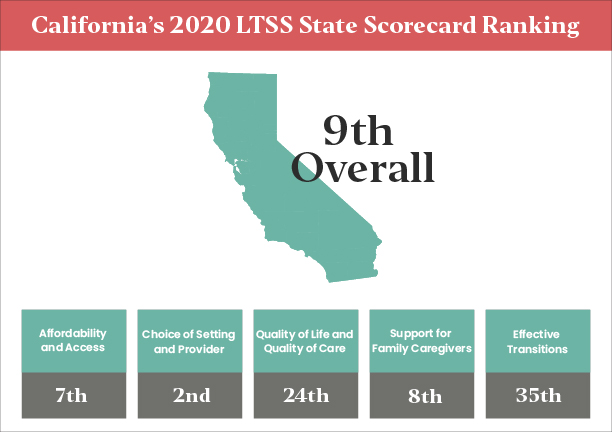

California ranked ninth overall on the 2020 LTSS State Scorecard, maintaining the same rank from 2017. This brief provides an overview of California’s Scorecard performance and key recommendations for transforming its LTSS system to better serve older adults, people with disabilities, and family caregivers.

Date Updated: 09/21/2020- california,

- caregiving,

- complex care,

- coordinated care,

- COVID19,

- dual eligibles,

- long-term care financing,

- ltss,

- master plan for aging,

- medicaid,

- medicare,

- person-centered care,

- quality measurement,

- scorecard,

- The SCAN Foundation,

Introduction

In September 2020, the AARP Public Policy Institute released its fourth Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) State Scorecard, comparing states on their efforts to create a high-performing system of care for older adults, people aging with a disability, and family caregivers. In the 2020 edition, Advancing Action: A State Scorecard on Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Adults, People with Physical Disabilities, and Family Caregivers, California’s ranking remained unchanged at ninth overall, underscoring that areas for improvement remain to ensure all Californians can access high-quality, affordable LTSS to meet their unique needs.1  While released in the midst of a global pandemic, the 2020 Scorecard reflects state performance prior to COVID-19. The pandemic has brought increased focus on the state’s LTSS system, revealing challenges and opportunities for reshaping how services are delivered and financed. Federal response to the pandemic has also allowed states new flexibilities to provide LTSS in ways that may create lasting delivery system change (e.g., virtual care management).2 This brief provides an overview of the AARP LTSS State Scorecard, and California’s Scorecard performance and key recommendations for transforming its LTSS system to better serve older adults, people with disabilities, and family caregivers now and in the future.

While released in the midst of a global pandemic, the 2020 Scorecard reflects state performance prior to COVID-19. The pandemic has brought increased focus on the state’s LTSS system, revealing challenges and opportunities for reshaping how services are delivered and financed. Federal response to the pandemic has also allowed states new flexibilities to provide LTSS in ways that may create lasting delivery system change (e.g., virtual care management).2 This brief provides an overview of the AARP LTSS State Scorecard, and California’s Scorecard performance and key recommendations for transforming its LTSS system to better serve older adults, people with disabilities, and family caregivers now and in the future.

AARP Scorecard Overview

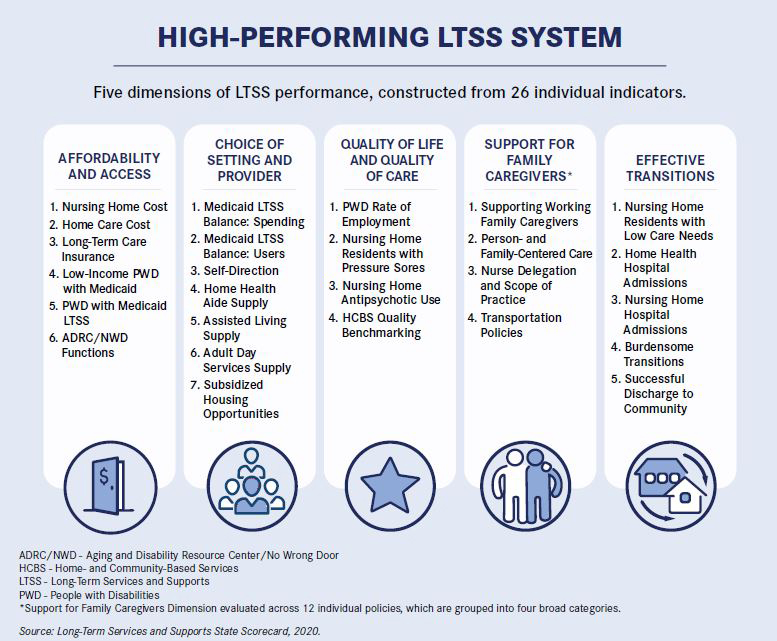

The AARP LTSS State Scorecard, funded by The SCAN Foundation and The Commonwealth Fund, showcases measures of state performance for creating a high-quality system of care. First released in 2011 and measured every three years, the Scorecard provides comparable data in order for state leaders, stakeholders, and others to benchmark performance, measure progress, and identify key areas of improvement. The following graphic shows the five dimensions of LTSS performance that are constructed from 26 indicators included in the 2020 Scorecard.

California’s Scorecard Performance

California ranks ninth in overall LTSS system performance in the 2020 Scorecard, which reflects the same standing as in 2017 and 2014. While maintaining its position in the top quartile of states overall, California improved in two dimensions and declined in two dimensions. Recognizing the rankings are in relation to the performance of other states, a review of individual measures within each dimension helps pinpoint opportunities for improvement. Table 1 shows California’s results followed by a brief explanation within each dimension. Table 1: California’s Rank in Dimensions of a High-Performing LTSS System, 2020, 2017, and 20141

| Dimensions | Definition | 2020 | Rank 2017 | 2014 |

| Overall Rank: | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| Affordability and Access | LTSS is easy to find and affordable. | 7 | 19 | 14 |

| Choice of Setting and Provider | A person-centered approach allows for consumer choice and control of services. | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Quality of Life and Quality of Care | LTSS maximizes positive outcomes while respecting the individual and his/her personal preferences. | 24 | 21 | 24 |

| Support for Family Caregivers | The needs of family caregivers are assessed and addressed. | 8 | 8 | 24 |

| Effective Transitions | Health care, LTSS, and social services are coordinated, minimizing disruptive transitions between care settings. | 35 | 22 | 22 |

Affordability and Access (Ranked No. 7): California ranks high for affordability and access in relation to other states, yet most Californians cannot afford the high cost of LTSS. The annual cost of 30 hours per week of home care averages $44,000, or three-quarters of median household income. The median annual cost of nursing home care is $127,750—more than two times the median household income. With only 4 percent of Californians age 40 and older having long-term care insurance, Medi-Cal becomes the primary payer for LTSS.1 Meanwhile, California’s patchwork of programs continues to be fragmented and difficult to navigate. People cannot easily connect to, and use, the services they need when they need them.3 Choice of Setting and Provider (Ranked No. 2): With California’s In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program representing nearly half of the national total of people enrolled in self-directed LTSS, the state ranks at the top for choice of setting and provider. Yet, the state’s proportion of total LTSS expenditures focused on home- and community-based services (HCBS) – 57 percent – is far below New Mexico (the top ranked state) at 74 percent. And, with housing impacting a person’s ability to access services in the community, the state trails behind with subsidized housing opportunities representing only 6 percent of all housing units. The state can do more to rebalance spending on HCBS and increase access to affordable housing to afford Californians real choice in where and how they receive LTSS.1 Quality of Life and Quality of Care (Ranked No. 24): California has consistently ranked low for quality of life and quality of care across all editions of the Scorecard as compared to other states. The state has seen marked improvement in decreasing the rate of inappropriate antipsychotic use in institutional settings to 11 percent However, where 37 states have implemented standardized quality measurement to benchmark HCBS quality, California has no HCBS quality measurement strategy utilizing any of the four available standardized LTSS quality measurement tools (i.e., National Core Indicators – Aging and Disabilities, Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems – HCBS Survey, National Committee for Quality Assurance [NCQA] Statewide Accreditation, and Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System – Emotional Support and Quality of Life Support Module). With over half of Medi-Cal LTSS funding going to HCBS, California needs to implement a standardized quality measurement strategy to ensure high-quality services that are responsive to people’s needs and comparable across states to spur improvement.1 Support for Family Caregivers (Ranked No. 8): California scores high in certain indicators including spousal impoverishment protections and paid leave policies for family caregivers. Yet, the state falls behind 41 states for assessment of a caregiver’s own needs, scoring a zero for no standardized caregiver assessment that helps identify need and link to services. California also continues to score low on nurse delegation allowing only 2 of 16 health maintenance tasks to be performed by home care aids (i.e., administer glucometer tests and enemas), while 18 states now allow registered nurses to delegate the full range of health related tasks to home care aids. California’s family caregivers continue to face challenges related to administering health maintenance tasks, including but not limited to tube feedings, ventilator care, intramuscular injections, and ostomy care. California can do more to identify and address the needs of unpaid family caregivers.1 Effective Transitions (Ranked No. 35): Nearly 1 in 10 California nursing home residents have low care needs, compared to 1 in 50 in the highest ranked state, suggesting that a significant percentage of California’s nursing home residents could otherwise be cared for in the community. Additionally, only half of individuals newly admitted to a nursing facility for less than 100 days were successfully discharged to the community. While California performs well in reducing the number of hospitalizations for home health patients, the state falls far behind in ensuring effective transitions from institutions to the community.1

Policy Recommendations

California has a strong foundation of LTSS programs, but system fragmentation and limited coordination, workforce challenges, and lack of financing options continue to impact system efficiency and access to services. A high-performing LTSS system requires an organized structure in which accurate information is easily available to enable individuals and families to identify what services best align with their needs and how to access them. The LTSS State Scorecard presents an opportunity to highlight progress and identify shortcomings in order to reform and strengthen California’s LTSS system. Additionally, this year’s COVID-19 crisis magnified this case for reform by exposing underlying vulnerabilities in systems serving older adults, people with disabilities, and their family caregivers. Prior to COVID-19, the state began to develop a Master Plan for Aging to serve as the blueprint for state government, local communities, private organizations, and philanthropy to build environments that promote an age- and disability-friendly California. In March, the Master Plan for Aging’s LTSS Subcommittee presented final recommendations to strengthen the LTSS system. Meanwhile, the state has utilized the flexibilities afforded by the federal government to ensure the state’s LTSS system responds to individuals’ evolving needs during the pandemic. Using the Scorecard to benchmark California’s performance on LTSS, the Master Plan for Aging as a roadmap for change, and the regulatory flexibilities brought forth through COVID-19, the state is primed to act. The SCAN Foundation recommends the following actions.

Leadership: Establish positions within the administration focused on leading LTSS systems change.

- Reorganize the state-level administration with a new Department of Community Living to promote coordinated, integrated person-centered care. People experience difficulties accessing services and supports needed to age with dignity and independence. Many of these challenges can be attributed to the fragmented arrangement of state- and federal funded LTSS programs across multiple state departments, with little data sharing and policy development focused on the needs, priorities, and experiences of older adults and families. This fragmentation impacts the ability to:

1. Plan and deliver services in a coordinated, streamlined fashion to individuals and their families, limiting access to necessary services and supports.

2. Identify population needs, and prioritize and plan services.

Recommendation: The California Health & Human Services Agency (CHHS), in collaboration with the California Department of Aging, should outline a plan for the state-level restructuring of state- and federal-funded LTSS programs serving older adults and people with disabilities through creation of a new Department of Community Living (DCL). The DCL would replace the current California Department of Aging, providing leadership in the delivery of home- and community-based LTSS with a goal of enabling all Californians, regardless of income and need, to age with dignity and independence. The structural reorganization would focus on coordinated, integrated service delivery to provide the leadership needed to implement system change that puts the person first and considers the whole system, rather than silos of existing programs.

- Ensure choice and access to coordinated, integrated service delivery for Medicare + Medi-Cal individuals. Accessing health care and LTSS is a cumbersome process for many older adults and families. All too often, individuals cannot access the range of services they need to remain at home, leaving them at risk of institutionalization. Dual eligible individuals – those eligible for Medicare and Medi-Cal – often face the greatest challenges, with significant health and functional needs that often fall through the cracks. Many individuals don’t understand their choices for integrated care, the benefits of integrated care, and how to access integrated care options. California needs a comprehensive vision to integrate and streamline services for this population, as well as a process to effectively engage individuals and inform them of their options.

Recommendation: The Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) should establish a Medi-Cal/Medicare Innovation and Coordination Office to lead all efforts around duals integration in the state. It should develop a vision and framework for integrated service delivery that will ensure California’s dual eligible individuals have access to an integrated care option regardless of where they live.

System Navigation/Coordination: Develop a comprehensive, statewide coordinated system of care.

- Ensure streamlined access to LTSS information and supports through a No Wrong Door system and streamlined state leadership. Many older adults, people with disabilities, and families face difficulty accessing the services and supports they need. They don’t know where to turn for help and don’t understand the existing service system to even know where to start. While there has been much discussion of a No Wrong Door system in California, it does not actually exist. A statewide No Wrong Door system offers an opportunity to develop a structure that enables individuals to access information on a menu of services versus a single program, with support in coordinating those services. Currently, only six of California’s 58 counties operate an Aging and Disability Resource Connection (ADRC), but these programs are limited in their functions as compared with other states. The LTSS State Scorecard provides several ADRC functions as benchmarks that could be used to strengthen the capacity of California’s ADRC program.

Recommendation: The California Department of Aging, in partnership with the departments of Health Care Services, Social Services, and Rehabilitation, should commit to expanding the ADRC model statewide while also expanding program functions and implementing a web-based portal that streamlines access to information and services.

- Develop and implement a standardized screening and assessment tool: For people who need timely access to LTSS, finding and enrolling for services can be cumbersome due to separate eligibility and assessment processes. This process can be frustrating and create delays in getting needed services. The current disjointed assessment system also fails to capture essential data for future system planning that identify unmet needs and gaps in California services.

Recommendation: CHHS should take the lead in convening relevant departments to prioritize the design and development of a standardized assessment tool that identifies an individual’s functional and social support needs, goals, and preferences as part of the process. A standardized assessment tool and protocol can streamline access to the range of supports needed to age with dignity and independence. Data collected through a standardized assessment could also inform state planning and resource allocation based on identified population needs and trends. The tool should be developed and implemented in alignment with current efforts to develop a standardized assessment tool and protocol for caregivers. It should also be fully incorporated into the development and implementation of a No Wrong Door system.

Transitions: Enable people to live at home as an alternative to institutionalization.

- Develop and implement a statewide strategy to ensure access to safe and timely transitions to the community. The LTSS State Scorecard finds that nearly 1 of every 10 residents in a California nursing home has low care needs. This means that these individuals could be cared for in the community as an alternative to institutionalization. But for many such individuals, the opportunities to transition either don’t exist or these individuals and their families do not realize there are other alternatives. Nursing homes are often the only option due to lack of home- and community-based alternatives, affordable/accessible housing, and awareness of alternatives.

Recommendation: The California Department of Aging, in partnership with the departments of Health Care Services, Social Services, and Rehabilitation, should implement a plan and strategy with specific outcome measures for ensuring institutionalized individuals have access to opportunities for transitioning to the community. Drawing from the LTSS State Scorecard, one such outcome measure should be to reduce the percentage of nursing home residents with low care needs by a targeted amount in a specified time frame.

Recommendation: The California Department of Aging, in partnership with CHHS departments, should establish a California Community Living Fund that would serve as a “bridge” program to provide services to individuals moving from an institution to the community, as well as individuals residing in the community who are at risk of institutionalization. The fund would address special circumstances that arise out of an eligible individual’s need for certain goods or services, or other conditions on a non-recurring basis. This would help individuals transition from institutional to community settings, or help individuals remain in the community and avoid institutionalization.

Recommendation: Conduct HCBS assessments and planning in nursing homes to support successful transition. DHCS should require transition planning within institutional settings that includes identification of individuals desiring to return to the community, assessment for transition, and preparing access to services in the community.

Support Family Caregivers: Implement policies to ensure the health and economic security of family caregivers.

- Reduce barriers for family caregivers to provide care. The aging of California’s population and increasing rates of disability have implications for all sectors of California and can no longer be viewed as a private issue for families. Approximately 4.7 million family caregivers in California contribute an economic value of $63 billion.3 Many are the “forgotten middle”—not poor enough for Medi-Cal and not wealthy enough to pay for private care.

Recommendation: The following three actions can improve the health and economic security of family caregivers:

1. The departments of Health Care Services, Social Services, and Aging should require the assessment of family caregiver need as part of an individual’s comprehensive assessment for publicly funded LTSS programs. 2. The state should implement policies that protect family caregivers from employment discrimination. New legislation was passed and signed by the governor in 2020 that would allow employees 12 weeks of protected leave for caregiving.4 3. CHHS, in partnership with the departments of Public Health and Consumer Affairs, should permit nurses to delegate more tasks to qualified home health aides, thereby reducing system costs and relieving caregiver burden.

Financing: Commit to resolve the LTSS financing crisis.

- Promote solutions to address the long-term care financing crisis facing older adults, people with disabilities, and families. California faces an unprecedented crisis related to the financing of long-term care. Typically, when paid services are needed, most Californians are not financially prepared. Individuals and their families initially pay for LTSS by utilizing their own resources, even though most people do not have the financial wherewithal to cover these costs on an ongoing basis. Most individuals have not set aside the size and scope of savings necessary for ongoing support to meet functional needs. State action is needed to enable families of today to plan and pay for their daily care needs of tomorrow. DHCS contracted with an outside entity to conduct an actuarial analysis to explore options for a feasible, effective solution to addressing the state’s long-term care financing crisis.

Recommendation: Based on findings of the actuarial analysis, DHCS should partner with the state treasurer as well as public and private stakeholders (including but not limited to the departments of Insurance and Managed Care, advocates, the insurance industry, labor unions, and academics) to propose options for an alternative financing mechanism to address California’s long-term care financing crisis. Additionally, these departments should explore ways to maximize engagement of new federal funding mechanisms, such as the coverage of non-medical benefits in Medicare Advantage plans to address social determinants of health for beneficiaries living with chronic illness and functional needs.

Quality Measurement: Implement standardized quality measurement strategies for LTSS.

- Use the LTSS State Scorecard to benchmark progress on Master Plan for Aging LTSS recommendations. Through the Master Plan for Aging process, the LTSS Subcommittee presented recommendations that align closely with key categories measured in the LTSS State Scorecard. The Scorecard lays out a vision for a high performing LTSS system. The state could use the Scorecard to benchmark broad system improvements as part of the Master Plan process.

Recommendation: The Master Plan for Aging should include measures from the LTSS State Scorecard in its measurement dashboard.

- Implement standardized LTSS quality measures. As California works to improve access to and quality of care for older adults and people with disabilities, there is a great opportunity and responsibility to build a strong quality monitoring and accountability infrastructure for LTSS. At this time, the state has not implemented standardized LTSS quality measures that can be used to compare LTSS statewide or across states.

Recommendation: DHCS should require Medi-Cal managed care plans to acquire National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) accreditation with LTSS distinction to establish a quality threshold for the state to compare quality of care between Medi-Cal plans. Additionally, the NCQA accreditation for case management could be used by community-based organizations contracting case management services.

Conclusion

California is at a pivotal moment. The COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally altered Californians’ lives, disproportionately impacting older adults, people aging with a disability, and family caregivers while also creating a massive budget shortfall. With these challenges comes opportunities and momentum for change, and the state has the tools to take thoughtful action. Drawing on the AARP LTSS State Scorecard as a benchmark to measure the state’s LTSS performance, the recommendations above, and the Master Plan for Aging as a roadmap, California can successfully navigate the changing environment and economic realities before us to forge a high-quality system of care. The SCAN Foundation thanks Jonathan Yoo for his contributions on the development of this policy brief.

Download the publication for all visuals and complete references.

Continue Reading

The SCAN Foundation aims to identify models of care that bridge medical care and supportive service systems in an effort to meet people’s needs, values, and preferences. Care coordination is a central component of this vision, which ultimately leads to more person-centered care. This brief outlines The SCAN Foundation’s vision for care coordination in a person-centered, organized system.

This policy brief describes California’s results in the 2014 Long-Term Services and Supports State Scorecard, identifying areas for improvement as well as policy opportunities to transform and improve the state’s system of care.

To succeed in this era of health system transformation, plans and providers bearing risk – in an accountable care organization (ACO) for example – will need strategies for managing a broad array of care needs for high-risk beneficiaries across multiple settings of care. Download this fact sheet to learn more.